The Role of Customer Service in Education

Earlier this week, I witnessed a college-level class argue with the professor about the due date of an assignment. Does it help the students to push the assignment back a week, or is it antithetical to good education?

Earlier this week, I witnessed a college-level class argue with the professor about the due date of an assignment.

The professor had planned to assign an exam, to be completed the next class meeting, that period. Several of the students, however, believed that they'd not received a fair chance to prepare for the exam. By "fair chance," they meant that they didn't fully understand the procedure of the assignment. That group lobbied---successfully---to have the syllabus amended. The exam was postponed a week. Meanwhile, in another version of the same class, following the same syllabus, taught by the same professor, they proceeded as planned and dutifully went away with their exam prompt. Was this an example of good customer service? The professor gave the students what they wanted: more time to prepare for the exam. Was that, however, what they needed?

The answer to that customer service question relies on the answer to another, more broad question: what is the purpose of education?

In examining this question, there are several different conclusions at which we could arrive. However, they largely fall into two camps: one goes to school to get a job; or one goes to school to change their community. Either education is pragmatic---utilitarian---or it is transformative.

Educational philosophers such as John Dewy would argue that education is a tool to create informed and capable workers. In his book, Democracy and Education, Dewey argues that while all communication is educative, there is a need to control and shape the context of the communication so as to create the most efficient learning environment. He states that educators "never educate directly, but indirectly by means of the environment" (p. 22). Because education, Dewey claims, is dictated by the environment, there exist certain things schools are effective at teaching. These subjects are those which a person wouldn't "naturally" learn through experience but which are required for adulthood. These are subjects like the "three R's"---Reading, Writing, and Arithmetic. Over time, these necessary subjects expanded to others as society's needs changed and the education system grew. Still, at the heart of the system was an idea of utility, of pragmatism. Children need to know how to read the news? Current events. The computing sector is growing? Teach the kids to code. You go to school to learn how to work.

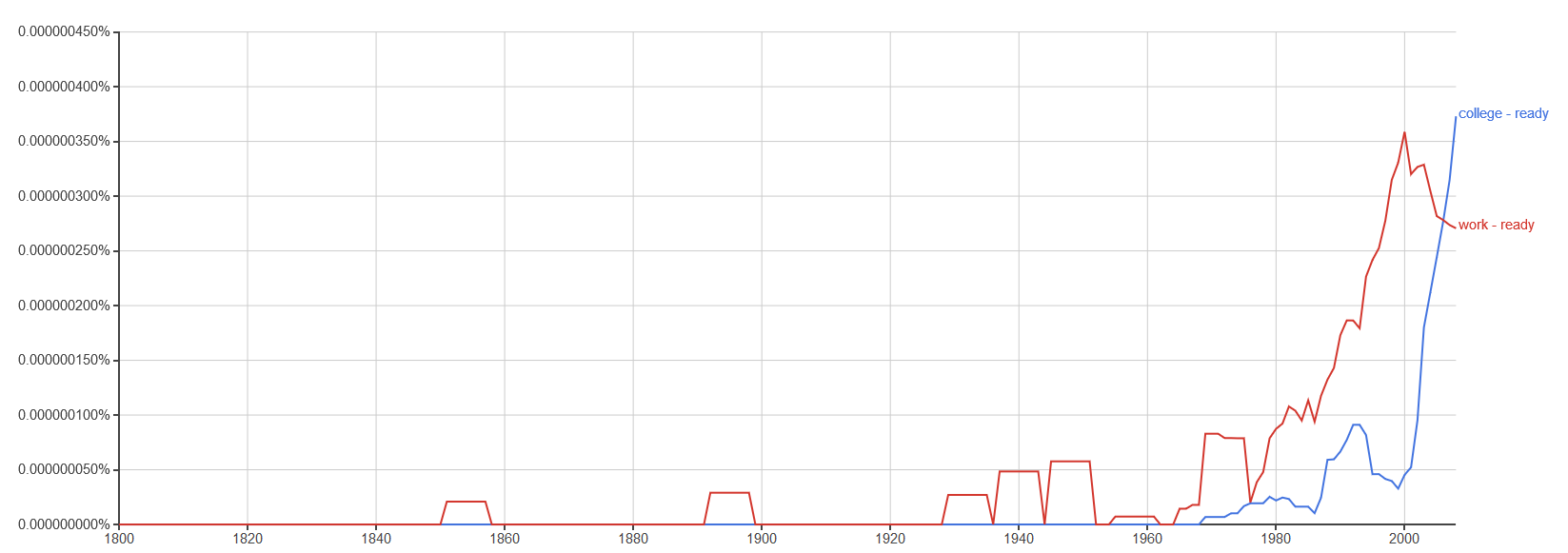

Around the start of the 2000s, we saw the push for college. College became the place to go, the advertising said, if a student wanted to be successful in life. No more was it a tool it get you a job; school was to prepare you for college.

In response to this trend, state departments of education began asking themselves what it means to be "ready for college." To answer that question, they developed the Common Core State Standards. The question for what to teach went from "what will get students jobs?" to "what will get students into college?"

Meanwhile, there was another movement, one arguing that education is transformative---that education is a tool to free the oppressed. In a Dewian model of education, the students are told by the teacher what is important; they are told what they must know. Education is a reaction to the context in which it exists. Students need to know how to read the news? Current events. The computing sector needs skilled programmers? Teach them to code. You go to school to learn how to work. Other theorists argue that this methodology is inherently oppressive. Where followers of Dewey see education as teaching students how to do, followers of philosophers like Paulo Freire see education as a tool to teach students how to confront their circumstances.

Freire grew up in post-depression Brazil, where he saw vast slums of poverty dotted with small pockets of extreme wealth. At a young age he saw education as the answer to his and his people's poverty. In response, Freire identified the characteristics of a flawed education system, the primary factor being the use of a "banking method" of education. In his book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire defines the banking method to be one in which "the students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor" (p. 72). That is to say, a lecturer stands at the front of the room, narrating facts to the students, whose goal is to "capture" these facts and memorize them. Freire argues that the very concept of a teacher-of-the-students is itself a problem because of the assumptions it perpetuates:

(a) the teacher teaches and the students are taught;

(b) the teacher knows everything and the students know nothing;

(c) the teacher thinks and the students are thought about;

(d) the teacher talks and the students listen---meekly;

(e) the teacher disciplines and the students are disciplined;

(f) the teacher chooses and enforces his choice, and the students comply;

(g) the teacher acts and the students have the illusion of acting through the action of the teacher;

(h) the teacher chooses the program content, and the students (who were not consulted) adapt to it;

(i) the teacher confuses the authority of knowledge with his or her own professional authority, which she and he sets in opposition to the freedom of the students;

(j) the teacher is the Subject of the learning process, while the pupils are mere objects. (p. 73)

Freire argues that students ought to be given the tools they need to transform the world, rather than to be beings bound by it. He argues that education must exist in dialogue (p. 80). Where Dewey may say that education exists in its own unique environment, Freire argues that education is inherently political. That is to say, that education shouldn't be a lecture from teacher to students, but it should be a critical dialogue between the students and the teacher such that the barrier between teacher and student, such that the barrier between oppressor and oppressed, no longer exists. You might, then, be wondering what a Freirian classroom, if it can be called a classroom, is like.

Deanna Fassett and John Warren explore this idea in Critical Communication Pedagogy. They, like Freire, argue that the classroom should reflect the "real world" because, well, it is the real world: "distinctions between a 'real' and some other world ... dulls our sense of justice, our need to be active, to resist, to effect change" (p. 62). Their belief is that a classroom is the place to "build a more just society" (p. 63). Central to their argument is that the classroom is performative---"like a rehearsal, my classroom is a place for imagining, for searching for possibility, for refiguring our lives toward some kind of future" (p. 70). Rehearsal is an apt word. Rehearsal, they argue, doesn't mean "practicing for the performance" because, even in the classroom, "we are performing" (p. 71).

Returning to the students in that classroom from earlier, we now have a framework to evaluate theirs and the professor's actions. If we accept that education is pragmatic and that students are customers of the institution---they are, after all, paying to be there---the move makes sense: it increases the chances of the students passing the unit because they get more time to prepare; they pay their money and get their grade. If, however, we accept that education is transformative, with a goal of modeling and influencing the larger world outside the classroom, the situation seems to become a bit muddied.

It isn't, though. Pushing back the assignment is, to use Fassett and Warren's analogy, akin to pushing back opening day in order to make changes to the script. It's not productive, it doesn't help the students learn, and it has the effect of giving them less time to complete the other assignments. What those students did was dig themselves into a hole they might not be able to dig back out of.

In this sense, customer service and education are diametrically opposed. The "customers" view the classroom, especially in a general education course such as the class in question, as a hoop to jump through in order to begin working in that "real world" outside school. In their best interest as a "customer" is delaying until their answers are "correct"---i.e., what the professor "wants." In the real world, much like in this particular classroom, correct answers and incorrect answers are not so black and white.